This week we’re taking a closer look at audience research. As I have touched on qualitative and quantitative data collection techniques in my post on market research, I will concentrate on persona (or avatar) marketing for this one.

I completed my Chartered Institute of Marketing Diploma in 1995. Avatar, or persona marketing was encouraged as an approach to targeting your market segment. This technique involves constructing a profile for a fictional person that represents your target market. If your target market can be segmented, you should construct a different persona to represent each.

While this approach might help the marketer to ‘speak’ to the target market as if they were a person that is known to them, I have always viewed this approach as risky. Perhaps even dangerous.

The thing is, people don’t necessarily fit perfectly into boxes. While some products or services might attract a certain, clearly defined, type of buyer, most won’t. The more detailed the profile that you build for your persona, the greater the chance you have of failing to recognise, or even alienating, a proportion of the true market for your product. This technique does encourage you to examine a broad array of the demographic characteristics and lifestyle factors for your fictional being: age, gender, educational achievements, job, which newspaper they read, family structure, location, what they drive, how they spend their weekends, which political party they vote for etc etc etc. You end up with a tightly defined profile for a person, which forms a pigeonhole. Then an integrated (and quite possibly myopic) marketing campaign is built, targeting people that fit that pigeonhole. When you think about it, how sensible is it to spend money trying to sell your product to someone that doesn’t actually exist?

That said, up until quite recently, I had been unaware of a better approach, and so I would advocate proceeding with caution, and being conscious to avoid over-profiling.

However, aware that it was over 20 years since I gained my marking diploma, and the emergence of the digital age in that time had provoked a paradigm shift in marketing (as well as all other areas of commerce), I decided to embark on a Strategic Social Media Marketing course from Boston University about 6 months ago. Things certainly have moved on in marketing in that time, and I was introduced to the concept of community (or network) marketing (personally, I prefer community marketing, as, back in the day, network marketing used to mean pyramid selling schemes that tended to have a negative reputation).

Community marketing involves the infiltration of existing online communities that are relevant to your product, industry or market. These communities serve the purpose of bringing people with a common interest together to discuss that topic and provide and receive value to/from that community. By finding relevant communities, you can more clearly identify the diversity of profiles that might be interested in your product. By just observing conversations, and the questions and answers exchanged, you can build up a good understanding of the the problems that these people want solved, and the pains that they want easing, helping you to develop your key value proposition.

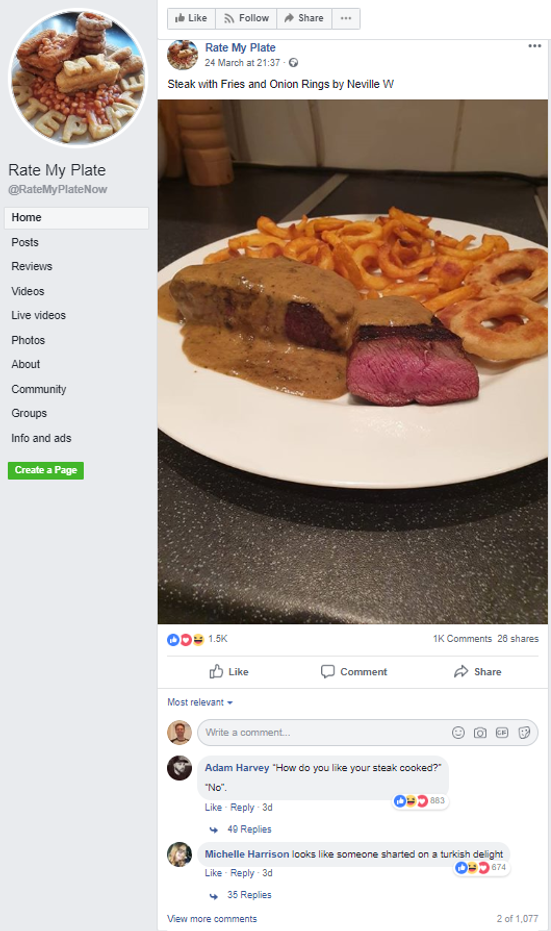

Communities can be found in many forms, for example as Facebook groups (particularly good for understanding user profiles), Twitter hashtags, independent chat rooms and forums, as well as blogs, Medium articles and Quora Q&As.

Without realising it at the time, this is how I had formulated the business model for my intended app based startup. This course just formalised the approach for me.

This case study illustrates my point nicely: About 3 years ago, I did some work with a small business (who have asked to remain anonymous) that turn domestic lofts into easily accessible storage space by installing insulation, floor boarding, lighting, shelving and ladders. They wanted to grow the business from being a local sole trader, into a national company, using a franchise model. They initially took a persona approach to selling franchises, and built a couple of avatars, which seemed perfectly logically sound: One avatar was a trades person with aspirations of running their own business, while the other was a person leaving the military services with some relevant skills (Defence cuts were driving large numbers in this segment at the time). Both seemed to be fairly sound assumptions, but focusing marketing efforts on these two profiles wasn’t generating as much interest as was hoped for. Many things changed with the business over time, but one of the key differences that made all the difference was a shift to more of a community approach to marketing. By engaging with a more general franchise community, they found an enormous uplift in enquiries from potential new franchisees. They were attracting interest from people looking for an attractive franchise proposition, and what’s really interesting is that, while some of their franchisees are from a trade background (as was expected), a good proportion of them are from the commercial sector, escaping the rat race of middle and senior management – a sector that was completely unexpected, and would never have been considered with a persona approach. The business is now on a roll, and currently have 16 fully fledged franchisees (including accountants, an ex Finance Director an ex Managing Director and other professionals) and a pipeline of new franchisees growing faster than they can process them – a nice problem to have. The business has also been shortlisted for the British Franchise Association’s “Emerging Franchisor of The Year 2019” award, and will know whether they’ve won in June.

I hope this last example will be viewed as constructive criticism…

I believe that the marketing for the MA Creative App Course has fallen into the persona marketing trap. I initially dismissed the course as it didn’t appear to be serving my needs. The overview provided was speaking to gamers and creative types, and I definitely don’t fit either of those personas. However, buried deep in the “Who Is This Course For?” section, there was just one line that suggested that this course might be what I was looking for: “Someone who has an idea of an app they wish to create”. It was this line alone that eventually persuaded me to investigate further. It was only an in-depth discussion with Alcwyn Parker that properly demonstrated that the course was right for me. Marketing materials need to spell out the value proposition for the reader, making the connection between the product features and the readers needs (i.e. the product-market fit) blatantly obvious. I suspect that it is my marketing experience that helped me to recognise that I needed to proactively seek out the value that the course holds for me. I wonder how many others haven’t bothered to put in the effort to find the value for them? I would recommend some A/B testing as it would be interesting to see how a community marketing approach impacts the level of interest shown for the course.

I am still yet to complete the Strategic Social Media Marketing course from Boston University. I only got half way through before the MA Creative App Development course commenced (I had intended to run the two in parallel for 3 weeks, but this module was more full on than I had anticipated). The course has provided plenty of very useful and relevant information so far, and so I will set a SMART goal to finish the course over the time of the next module:

Specific

I will improve my understanding of strategic digital marketing by completing the Strategic Social Media Marketing course from Boston University.

Measurable

The course will give me a good insight into how digital products are marketed online and introduce me to tools that I can use to help with market research.

Achievable

There are approximately 24 hours of study remaining to complete the course, which I can schedule across the 12 week period of GAM730. The course is perfectly pitched at my level of capability.

Relevant

Familiarity with digital marketing techniques and tools is very important for app marketing and continuing market research throughout the product lifecycle.

Time-Bound

I will have completed the course by the 26th August. With 24 hours of study left, I will dedicate 2 hours per week for 12 weeks over the course of GAM730.